Written by

Doug Hostetter, Member of the Pax Christi International United Nations Team

In cooperation with

Amgad Al-Mhalwi, Staff of Al-Najd Developmental Forum

March 2024

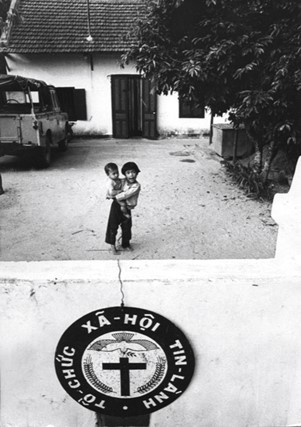

Before joining the Pax Christi Advocacy Team at the United Nations, I directed the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) United Nations Office in New York for more than a decade and co-chaired the Israel/Palestine NGO Working Group Israel/Palestine at the UN. MCC supported several NGOs that were doing relieve, development and peace work in Israel and Palestine. On visits to Gaza, I became friends with several staff members of Al-Najd Developmental Forum, one of the MCC supporting NGOs with headquarters in Gaza City. Al-Najd, with Mennonite support, helped Gazan families develop home gardens and raise rabbits & chickens.

I have kept in touch with two of the Al-Najd staff over the years through Facebook Messenger. After the Hamas attack on October 7 and the Israelis response of massive bombing, I soon learned that in the early bombing the building that housed Al-Najd was completely destroyed and Mostafa Al-Naffar, one of my staff friends there had also been killed. My remaining friend, Amgad Al-Mhalwi, who has worked at Al-Najd for 17 years, has continued sending me updates on his family.

Amgad’s family, originally from Hamama (25 miles north of Gaza), but in 1948 Israeli military forces drove the family out of Hamama to the Nuseirt refugee camp near Gaza City, in what the Palestinians call the “Nakba” (“the catastrophe,” when during the creation of the state of Israel, the Israeli army forced the evacuation of more than 400 Palestinian villages). Amgad (36) and his wife Qamer (25), both former university students, married five years ago and now have two boys, Majd (4) and Ibrahim (2 and a half). Amgad and Qamer lived with his extended family of about 50 people in a compound of houses near Gaza City. When the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) ordered everyone to leave northern Gaza in the first week of the war, several of Amgad’s extended family were killed while trying to travel to the south as ordered. Amgad decided that it was safer to shelter in the north rather than getting killed trying to go south.

“We left our house first to my aunt’s house, then to my uncle’s house, then to my wife’s family’s house, then to Al-Huda School in the Sheikh Radwan area, and after that, Ramez Luxury School, then Musab bin Omair School, and the finally to Umar bin Aas School.”

Each time that they moved, it was because of shelling and bombing in that area, but actually there was no safe place to go.

The Umar bin Aas school was already overcrowded but Amgad found a classroom on the third floor of the school (about 5 X 5 meters) which provided a safe, if crowded, refuge for the 55 people of Amgad’s extended family.

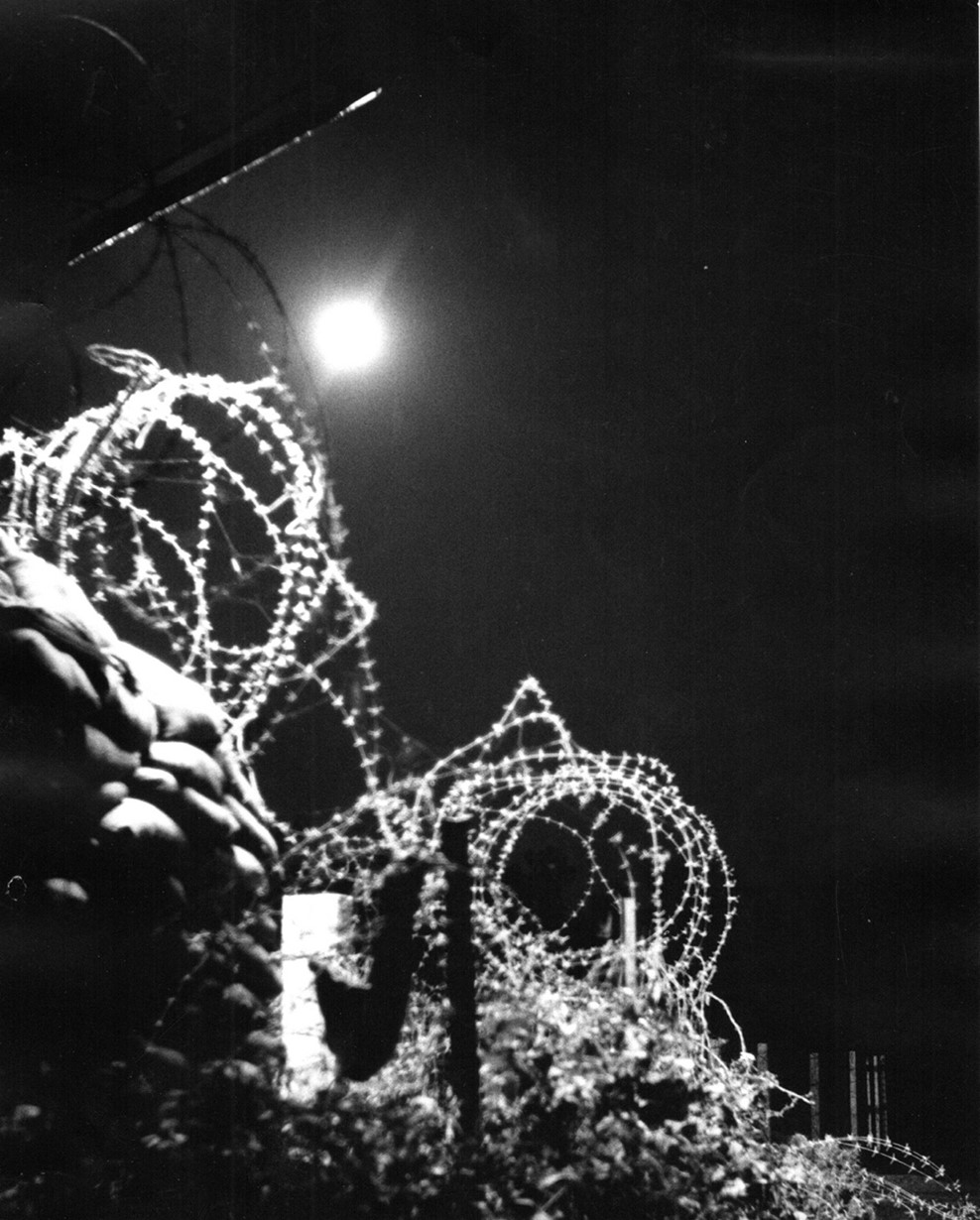

The school seemed secure until November 19, when the IDF moved into the area and started shelling.

“My brother, the shells were everywhere. They were all around, next to the school. Many of the children who were in the school courtyard were injured and died. A shell came behind the school and people began to flee under the bombardment.

We said, ‘What do we do? Where do you go under heavy bombardment?’ We decided it was safest to stay in school.

I was just outside the classroom door when, shortly after the afternoon prayer, at 3:20 PM a tank shell hit the classroom wall sending shrapnel throughout the classroom. The explosion blew me away from the door, and when I reentered the classroom, it was full of blood and screaming.

My beautiful father is dead, and my uncle’s wife does was not moving, and my sister’s neck was sliced open. I am crying, and my brother was praying, he died while praying. My wife face is bloody, her whole body is covered in blood. She is crying and screaming, and my children are crying and screaming, my whole family is screaming. I was in shock, uninjured and watching everyone scream.

The most beautiful people in the world died that day. My father, the most affectionate person in the world, my brother who loved my children so much. My sister, who in my heart was more like my daughter, and my aunt was the 4thmember of my family to die in that room.

Thirty people were killed in the school that day and over a hundred were wounded. Three shells hit the school while we were there, and a 4th exploded as we were fleeing, and I don’t know how many hit later.

I carried my two children and took my wife, sister, and brother to the nearest medical clinic.

My older brother told me that he would bury my dead family members. I was unable to say goodbye to any of them. The bombs and shells were falling, and I had to try to get my children to safety.

It was the worst day of my life.

Both of my boys had been in the room by their mother when the shell hit that night. They had witnessed their grandfather, their uncle, and their aunt being killed, with blood all over everyone in the classroom. My sister was bleeding profusely from her neck, my cousin had his hand severed, and shrapnel had destroyed both of my brother’s eyes. The boys were screaming, quaking in fear and peeing in their pants”.

I did not hear from Amgad for a month and a half and was worried that he and his family had been killed in the massive bombing. Amgad and family miraculously had made their way, mostly walking, the 20 miles from Gaza City to Rafah on the Egyptian border. I finally got a short message:

“We are in Rafah. My family is tired, sick and cold. We do not even have a tent to live in”.

Amgad eventually was able to buy a nylon tent for $400, but there was no heat, and food and water were very hard to find.

“The children became sick. We need psychological support and food. We are very tired. We long to return to our homes, even though they are destroyed.

The experience of that night in the bloody classroom has changed my boys. Najd now always wants to sleep with Amgad and Ibrahim always wants to sleep with Qamer. When the boys heard bombing, they wet their pants and ran terrified to their parents. If they see red, even a piece of clothing, they run away screaming, blood, blood, blood”.

On February 12 the Israeli Defense Forces rescued two Israeli hostages in Gaza. To distract from the IDF operation to rescue the hostages, they bombed and shelled other areas of Rafah killing at least 67 Palestinian women and children.

Amgad and his family were living in a nylon tent in Rafah that night, February 12th.

“Tonight was very difficult

Very strong bombardment

I saw my son Majd trying to hide from the bombing

He was trembling as he tried to hide his face in the ground, thinking that if no one could see him, he wouldn’t die.

Food, money, water for me, that’s ok, but here we are not safe. We need safety.

Please pressure your government to end this war and the occupation.”