This blog post originally appeared on the Mennonite Church USA website.

By Doug Hostetter

Doug Hostetter is the peace pastor at Evanston Mennonite Church (which he attends digitally), and is the associate representative of Pax Christi International to the United Nations in New York City.

Many Mennonite homes in Harrisonburg, Virginia, had guns in the 1950’s. No, we were not worried about “personal protection” — most of our neighbors never even bothered to lock their doors — but we lived on the edge of farmland, surrounded by wonderful state parks. Like most of my male friends, I grew up owning guns and looked forward to hunting season in the fall. I was totally comfortable around guns. I had been taught gun safety by an older Mennonite neighbor before I was allowed to buy my first rifle. The first and most important lesson always was: Never point a gun, loaded or unloaded, at another person. Guns were to be used for target practice, until one learned to use them accurately, and then, for hunting, carefully following safety precautions so that one didn’t accidently kill a protected animal or injure another hunter. Our Mennonite faith taught us that personal safety comes not from guns and locked doors but from personal relationships that can be built, even with one’s enemy, through integrity, trust and vulnerability.

After graduating from Eastern Mennonite College (now University) in 1966, I filed for and received conscientious objector status. As this was the middle of the Vietnam War and men of my generation were being drafted and sent to Vietnam against their will, I felt it was only just that I volunteer to do my alternative service in Vietnam as well, but I served with the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC). MCC at that time was the director of Vietnam Christian Service (VNCS), which also included volunteers from Church World Service and Lutheran World Relief. I was assigned to start a VNCS unit in Tam Ky, Quang Nam, in central Vietnam, where the heaviest U.S. military activity was taking place at that time. Our primary project was a literacy program that utilized 90 Vietnamese high school students to teach 4,000 refugee children how to read and write their own language, after the schools in their home villages had been destroyed by the American Air Force.

Experiencing life in Vietnam during the war was a total shock to my system.

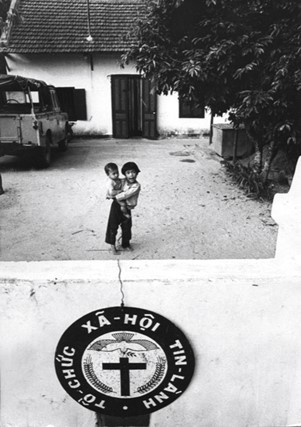

Wall around the VNCS house. Photo by MCC.

I had grown up feeling very comfortable and safe around guns, which were being used responsibly by neighbors for hunting. Now, I was in a country at war, with nearly a half-million American soldiers bristling with guns that were designed for killing other human beings.

I learned a lot about protection and guns during my three years in a war zone. When I visited Tam Ky to explore whether VNCS should start a unit there, I had been informed by the American officials that the only safe place for me to stay in Tam Ky would be in one of the U.S. government compounds. There were three options: the Military Advisory Command, Vietnam (MACV); the CIA compound; or the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) compound. All three compounds were heavily walled and guarded with land mines and machine gun posts.

Wall around the USAID compound. Photo by Doug Hostetter.

I stayed in the USAID compound, but I soon realized that I could not remain there. Vietnamese people were allowed to come into and leave the USAID compound during the day, but at night, all Vietnamese people — except prostitutes — were expelled, and Americans were not allowed to leave the compound in the evening. I realized that, if I was there as a Christian peace witness to the Vietnamese people, I could not live in a U.S. Government compound, where I could not interact freely with Vietnamese people. When I returned to start the VNCS unit in Tam KY, I and one other VNCS volunteer moved into one of the dorm rooms of the local Catholic high school that the priest had built for students whose homes were far from the school.

Eventually VNCS was able to rent a small bungalow across the street from the Catholic high school for our unit house. I will never forget the advice we received from the woman who rented us the bungalow. Mrs. An explained that, occasionally, the National Liberation Front (NLF, which the Americans called the VC) would briefly take over Tam Ky. She pointed out that, since the house was fenced in by only a small four-foot wall, we could add a steel gate, a few rolls of concertina barbed wire for the front and top of the wall, and a 50-caliber machine gun for the front yard. That, she thought, would be adequate protection, so that when the NLF guerrillas came into town, we could hold them off with the 50-caliber until the U.S. Marines arrived to rescue us. No, I explained, that was not how we wanted to live. We never put a gate in that four-foot wall, and everyone in the village knew that we had no weapons. Our only protection was a small sign “Vietnam Christian Service” (in Vietnamese), with a peace dove and a cross. The VNCS house was the only place in Tam Ky where Americans lived outside of walled and guarded compound. I lived in Tam Ky for three years. The National Liberation Front took over the village — often for only a few hours in the middle of the night — about a dozen times. Each time that the NLF entered Tam Ky, they attacked the heavily guarded MACV, the CIA and the USAID compounds, but the VNCS bungalow, the one unprotected place where Americans lived, was never attacked.

I came to realize that most people in a war kill

to keep the enemy from killing them first.

When it was clear to everyone that we had no weapons, and in fact could not even protect ourselves, we were no longer a threat; we were not feared and many Vietnamese people, on both sides of that war, became our friends.

My attitude towards guns has changed drastically since Vietnam. I have seen, up close and personal, the way military weapons destroy the human body. It astounds me that my country, or any nation, would allow civilians to purchase military style automatic rifles, like the AR-15 or the AK-47. These automatic rifles were specifically designed for war — to kill and or seriously maim people.

Why would any government allow the sale of automatic rifles to the civilian population, and why would any decent person want to own such a weapon?

I am not philosophically opposed to hunting, and some of my brothers still do, but since returning from Vietnam, I have not been able to bring myself to reassemble my boyhood .22 caliber rifle, which I had carefully disassembled and stored before I left for Vietnam, over 50 years ago. I do know, both from the Sermon on the Mount and personal experience, that true safety comes not from higher walls or bigger guns but from the refusal of weapons and hostility, which can enable trust and friendship whether with neighbors at home or enemies abroad.